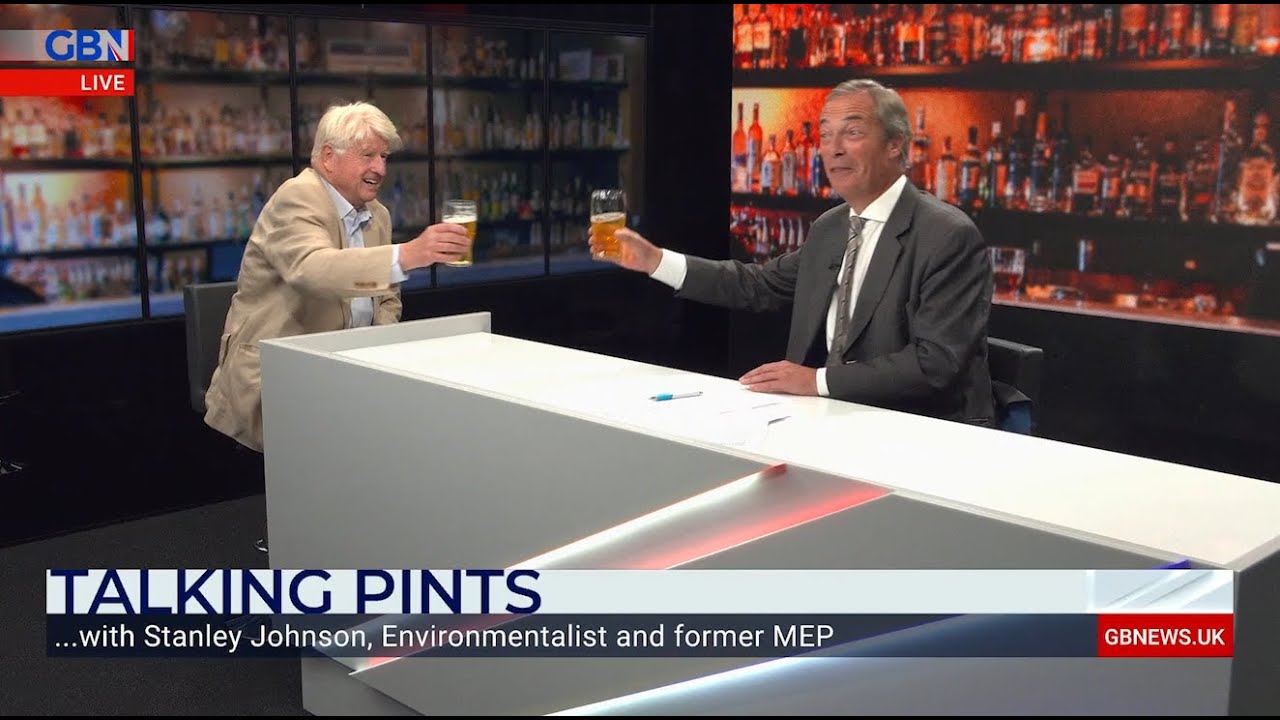

Talking Pints

Niall Ó Conghaile reviews the bizarre outcomes of the post-Brexit metric review. Talking Pints was originally published by East Anglia Bylines. Historically Britain has led the way in setting international standards. So will the pint bottle of champagne return in a post Brexit world?

Following Brexit there was a lot of excitement in the UK about the possible return of the pint bottle of champagne. Apparently, this size of bottle was much beloved of Winston Churchill, and so for reasons to do with winning the War (?) it was important that the pint bottle return.

The claim had become widespread before Brexit that the pint bottle had been banned by metrification and the diabolical Brussels bureaucrats. Of course, it was all nonsense. Pint bottles of cider, for example, are widely available under European law.

So why can’t you get pint bottles of champagne?

It’s because of regulation and standardisation. Just not in the way that you might think.

The 750 ml bottle is now almost the global standard. However, in the past in France (and indeed Europe) non-standard bottle sizes were common.

Over time the variations reduced to the few that remain today in your local Auchan, Lidl or Kaufland. But why are Britons forced to drink the continental 750 ml and not a true British pint of champers?

Actually, the 750 ml is British, or at least “for Britain”. Dealing with all those irregular wine bottle sizes, and an irregular number of bottles to the case, was an irritant to the wine merchants and wholesalers of London in centuries gone by.

Why would a château in Bordeaux care?

The UK for much of the 19th century was the richest country in the world and had the richest middle class with the most disposable income. The UK was the largest importer of wine – other big consuming countries drank their own.

Moreover, the wholesalers in London were also often suppliers to British colonies and much of the rest of the world – in both the actual Empire, and the informal Empire. In places like Argentina, Britain was often the centre of the world. Hence the standards set in London became international standards.

Incidentally this British influence can also be seen in other ways in the world of wine, including the taste and types of fortified wines exported.

Standardisation meant that the pint bottle, for most wines, was effectively the Betamax of vessels: something to be nostalgic about, sure; but too costly to continue producing separately.

So who is the dominant force now?

The UK remains an important market for wine, of course. But it is very far from dominant.

Nowadays wine producers and the “Place de Bordeaux” market tend to have prices (especially at the top end) set by the United States and increasingly East Asian markets. This is even starting to change how the wine is produced and how it tastes.

The old wine markets of Europe, like London, that used to set the prices, have gone by the wayside. Now they just remain tram-stop names, and squares in old towns.

Post Brexit Britain is somewhat in the same position

Policymakers in the UK have to adjust to the reality of no longer setting international standards. The UK no longer offers markets of bulk. Nor does it have recognised high standards that others are keen to adopt.

Such realisation is painful, for sure. But isn’t it healthier than trying to keep up with the European and America behemoths. After all, Australia and Switzerland don’t try to have their own “world-leading standards”.

Yet many Brexiteers, and some in the Labour Party, seem to have difficulty in adjusting to the UK’s new place in the world.

Why are they finding their new role vis-à-vis standard-setting and regulation so hard to understand?

Once you accept that it’s inevitable that you will accept European standards, then the point becomes, why not get the full benefit of common standards by being inside a single market?

That’s the journey for the UK.

À la nôtre!

Thanks to Niall Ó Conghaile and East Anglia Bylines for allowing us to spread this important story more widely! 🙂

Look at Gina Miller’s position on Rejoining EU

We leave you with a punk rock song about the difficulty of ordering two pints of lager and a packet of crisps – based on Max Spodge’s difficulty in being heard at the Tramshed in Woolwich – it was impossible to procure said 568 ml of light ale in the 1980’s … Splodgenessabounds were an oi band which the editor played with in days of yore … I doubt Max had foreseen the problems of Brexit, but just as a soft landing for this article …