By Adrian Ekins-Daukes

One year ago we were at the height of the first wave of the coronavirus pandemic. Even before, the Royal College of Emergency Medicine was warning that acute care was struggling, emergency departments were under-resourced and overcrowded, and often outdated in terms of facilities and equipment. However, this article is intended to give a snapshot of conditions 12 months ago, not a full history of preceding events.

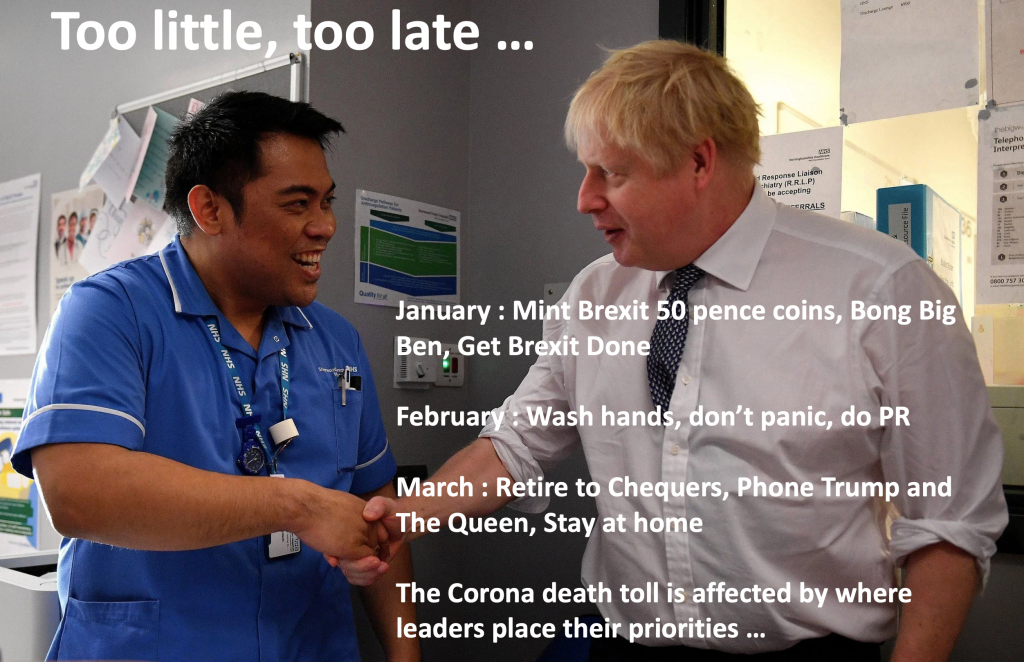

On 21 March 2020, 10 Downing Street put out the following statement on the situation :

“Our response has ensured that the NHS has been given all the support it needs to ensure everyone requiring treatment has received it, as well as providing protection to businesses and reassurance to workers. The PM has been at the helm of the response to this, providing leadership during this hugely challenging period for the whole nation.”

This complacent and self-congratulatory declaration was issued on a day when the television news featured distressed NHS workers in fear for their lives because protective equipment was either unfit for purpose or lacking altogether. It is false in every respect.

Far from being at the helm, PM Johnson spent much of February at his country retreat, Chequers, with Carrie Symonds, then his new fiancee. His occasional visits to London seemed more about social appearances and Conservative fundraising than the nation’s affairs. During January/February he missed five consecutive meetings of the emergency “Cobra“ Committee during when the pandemic had been on the agenda, Only on March 2 did he take over the chair, when the virus was firmly established. Then, for a further 3 weeks, he toyed with an impractical policy of herd immunity instead of immediate lockdown. This dithering cost over 20,000 lives and has probably cost more since that time.

Regarding support for the NHS, a leaked email disclosed on 18 March 2020 that some hospitals were just 24 hours away from running out of protective equipment (PPE) for nurses and doctors. Shortages included visors, masks and gowns. and some other items had run out entirely. In another email, to directors of infection control, NHS England said that there were no visors left nationally, no long sleeve disposable gowns, only goggles suited for flu.

This situation was confirmed by television and newspaper interviews with hospital staff over this period. One hospital manager who confirmed his hospital did not have enough PPE equipment to last the next 24 hours said that they’d been told specialist respirator masks would soon run out nationally and only less suitable masks without visors were available. Eye protection and long sleeve aprons had run out and they were buying safety goggles from industrial wholesalers. The previous night he’d had to ration equipment across four wards – normally one ward would have held 10 times that amount. Asked what they made of the claims there was enough stock in the country, he added:

“We’ve been told for weeks that there’s stock, there isn’t”.

Towards the end of March, one regional NHS director of procurement said he was unable to get hold of any gowns from the NHS supply chain, exclaiming in desperation “God help us all.” The GMB union said the lack of PPE and testing for frontline workers was “a national crisis”. Ambulance workers were not being given access to PPE, even when being sent to treat patients suspected of having Covid-19.

The consequences for patients of the delays and lack of essential equipment was horrendous, especially for the elderly. Some hospitals were overwhelmed and a system, drawn up by the Governments chief advisors, was introduced to select which Covid patients should receive intensive treatment. This was a death sentence to anyone over 80 or with a serious underlying medical condition; in practice it was also applied to many over 60. These patients were consigned to death wards where they received little or no nursing treatment or even attention . Steps were taken to conceal this from the public, but some witnessed the conditions in which their dearest were to die.

The government failed completely to give the NHS and patients the support needed at the height of the crisis. Its ‘reassurance’ to NHS workers was non-existent.*